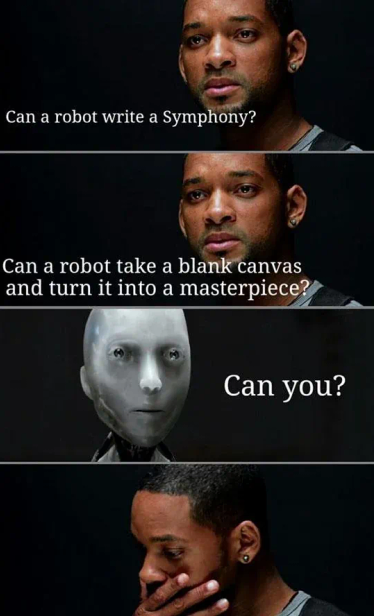

I find the tension concerning the use of AI tooling in the open source community interesting.

On the one hand, here we have a community who believe code should be openly shared and can be used for any purpose; that's encoded in the license.

The only difference of opinion is whether the license should enforce this openness.

But there's also a very strong reaction by many in the same community to training AI on open source code.

Emotion is a large part of both beliefs: wanting to use open source, or against training AI on it. Emotional reactions are legitimate. There must be an underlying believe system that evokes both.

I can see this as "rage against the system" except that many of the same people do not seem to react as angrily if open source code is used by that same system in other ways. Even free software purists accept this reuse, as long as the source remains open.

Perhaps it's that this use of open source source code was never expected: you'd either reuse its functionality OR learn from it as a human. Machine learning doesn't fit that.